Karl Brown, Head of Sustainability, recently contributed to the Summer edition of ACES Terrier. Aimed at public sector bodies across the UK, the Terrier features content from a range of sources which comment on public sector assets.

Karl’s article focuses on the decarbonisation agenda and local governments’ roles across the UK, with a particular focus on how collaboration throughout the construction industry is key to achieving targets.

Introduction

There is an almost overwhelming amount of information available on the topics of decarbonisation and sustainability and sometimes it’s difficult to know where to turn. On the back of COP26, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC’s) latest findings and ahead of Phase 3b of the government’s Public Sector Decarbonisation Scheme, at HLM we’ve been thinking about what this all means for the future of our public sector estates.

The IPCC state that greenhouses gas emissions must peak by 2025, and be halved by the end of the decade, to give the world a chance of limiting future heating to 1.5C above pre-industrial levels. At COP26, the UK government reiterated its commitment to reach net zero emissions by 2050. The ‘Net Zero Strategy’ sets out how the UK will secure 440,000 jobs and unlock £90bn of investment by 2030 on its path to becoming a net zero carbon economy. It is likely these ambitions will need to be ramped up in light of the latest IPCC report.

In the UK, 300 out of 404 (74%) of District, County, Unitary and Metropolitan Councils and 8 Combined Authorities/City Regions have declared a Climate Emergency to date. (Climate Emergency UK, 2022) These authorities will have to tackle a wide range of issues including transport, land-use and energy across a range of sectors and the transition will have a big impact on all aspects of our lives. Specifically in relation to the built environment, the public sector estate has a huge task to reduce the carbon emissions associated with the construction and operation of buildings whilst creating sustainable, biodiverse, flood and drought-resilient places.

The role of Local Government

Local authorities can not only facilitate, but lead the decarbonisation process of our built environment, be that through infrastructure projects, improved efficiency and utilisation of existing buildings or the commissioning of net-zero carbon retrofitted and new buildings.

The vast range of estates and buildings in the control of local authorities can make this a daunting proposition. Consider also the number of vacant and brownfield sites under control of the public sector and it is clear that there is considerable scope to shape the future of our built environment. Taking housing as an example, the UK has one of the oldest and poorest performing housing stocks in Europe. Coupled with the current energy crisis we now see 6.5m homes in fuel poverty. (Fuel poverty data is at odds with the current cost of energy crisis, n.d.)

Councils are ideally placed to deliver programmes to decarbonise our housing stock. Specifically, councils can deliver retrofit programmes for public buildings, local authority-owned housing, and fuel-poor households more broadly. A widescale, national retrofit programme would include energy efficiency measures and the installation of low-carbon heat sources. Energy efficiency should be seen as a major resource in the context of local and national efforts to achieve sustainability targets and in creating more equitable and just communities. Clearly, this needs to be funded. Many would like to see a more ambitious implementation of a ‘Green New Deal’, but local authorities do have other mean. Receipts from the rationalisation of estates, greater collaboration with the public sector and scaled back estate requirements to deliver core services will help fund such a programme.

It’s not just in the domestic sector where local authorities can have a significant impact, they own and manage significant real estate portfolios with historic building stock and the same energy efficiency issues. Throw in a vast range of building types, ages, heritage assets and the legacy of mid-twentieth town planning and the complexities and practicalities of upgrading building performance can be intimidating.

The benefits of energy efficiency

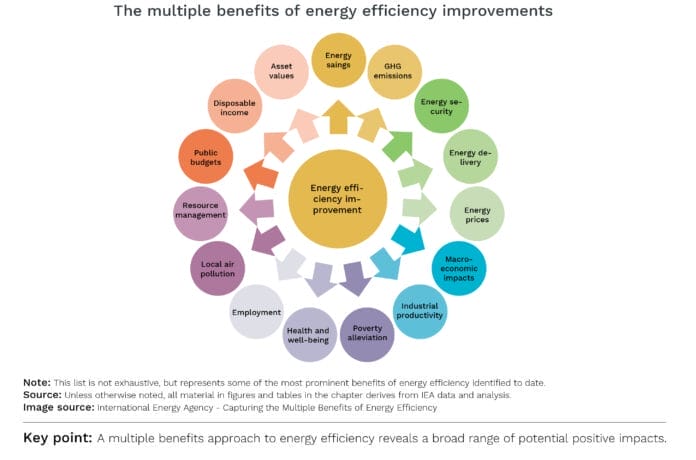

However, the outcomes of energy efficient improvements align with the goals of the public and of policy makers, be that in lessening the impact of rising energy bills, providing climate resilience, reducing costs from extreme weather incidents, or having a positive impact on human health and wellbeing.

There’s a bottom line to this too. Directly, reducing energy demand lowers energy bills and saves money, something that has never been more important than now, amid ever-rising energy prices. Indirectly, creating a market for improving the fabric performance of our existing building stock – through a programme of deep retrofit works – creates jobs. (Capturing the Multiple Benefits of Energy Efficiency, 2014)

The Local Government Association commissioned a report in 2021 (Delivering local net zero) that demonstrated how going beyond the status-quo can create significant value to local communities. The report concludes that retrofitting 3.49 million homes to Energy Performance Certificate (EPC) C by 2030 would:

- Save £698m from energy bills by 2030.

- Reduce carbon emissions by 7.92MtCO2e by 2030.

- Reduce costs to the NHS by £1.9bn per annum.

- Create demand for 23,000 new skilled workers.

How can the construction industry help?

We therefore must ask, what are the practical implications of an energy efficiency and decarbonisation strategy and how can the construction industry help?

Public sector organisations often accumulate large portfolios of space, buildings, and land over time, which can be overwhelming to evaluate and develop whilst maintaining existing services. What is needed – and where HLM’s ability in this area lies – is a guiding hand to develop strategies that make their assets work for them.

The first step to creating effective and sustainable estates is to understand the existing portfolio and how it can be better optimised and adapted to best address needs within communities. This comes from the detailed study of buildings to understand their condition, capacity, fitness for purpose, utilisation, and energy performance. Often, the best solutions are those which need no new buildings at all but instead propose careful adaptation, reuse and retrofitting to supply modern, hybrid work environments or comfortable, healthy homes.

Any presumption that a new building is the solution should always be challenged. The right solution will ultimately be a cost-benefit analysis but one that must ensure non-financial costs and benefits are factored in to capture, for example, improved health and wellbeing of occupiers.

Once the decision has been made to reuse an asset, then a programme of deep retrofit works should be planned, designed, and constructed to the highest possible standards. PAS 2035 and PAS 2038 provide a framework for the retrofitting of domestic and non-domestic buildings respectively and the Association for Environment Conscious Building (AECB) and EnerPHit (published by the PassivHaus Institute) provide standards and targets for designing, testing, installing, and inspecting retrofit projects. By insisting on these standards and defining ambitious targets, local authorities can lead the way in a retrofit revolution.

Making better use of existing buildings has another benefit, it reduces the embodied carbon of construction; embodied carbon being that emitted producing a building’s materials, their transport and installation on site as well as their disposal at end of life. In the UK, 49% of annual carbon emissions are attributable to buildings and 20% of those relate to the embodied impact of new construction.

Whole life carbon impact

To date, much of the construction industry’s focus has been on reducing carbon emissions from operational energy.

As buildings decarbonise – through improved energy efficiency, electricfication and renewable energy generation – the operational carbon of buildings reduces, meaning that the embodied carbon of a building becomes a significantly higher percentage of the whole. Whilst this will vary by building type, it is estimated that embodied carbon emissions represent 40-70% of the wholelife (operational + embodied) carbon of a new building. For eexample, the embodied carbon in the sub and superstructure of an office building can typically be around 65% of the whole and therefore substantial reuse of a building’s structure retains carbon and reduces the wholelife impact of construction. (LETI Embodied Carbon Primer)

Councils are already taking a leading role on decarbonisation and at a time when they are resetting following the pandemic, driving a green recovery. The effects of the changing ‘high street’ and ‘hybrid working’ have been well discussed; in my hometown of Sheffield, circa 70% of Fargate’s commercial space, once the main shopping street, is now empty. Reimagining the purpose of town centres is another part of the bigger challenge – increasing footfall by creating rejuvenated, inspiring, inclusive places that people want to visit – but how can we ensure we harness heritage when buildings are not fit for purpose? In order to fully embrace a circular economy, we need to change the historical, linear lifecycle from “take-make-use-dispose” to a circular “take-make-use-disassemble-reuse”. This requires not only a significant upskilling across the industry, but a whole re-imaging of the industry itself.

One of the barriers to this approach within the construction industry is the skills gap. Currently, the training of many industry professionals does not include sufficient focus on sustainability or retrofit, requiring people to voluntarily upskill. But few people want to deal with leaks, asbestos, and heritage issues – it’s complex and difficult, and can be expensive (for everyone!). At HLM we are upskilling our people through the AECB’s CarbonLite Retrofit Course to supplement our team of PassivHaus designers and to deliver net-zero carbon buildings. Ultimately, we want to see the same standards applied to refurbishment as new build and accredited to AECB and EnerPHit standards. It can often be easier and cheaper to design new, and the challenge can scare people, as opposed to being seen as an opportunity.

What can Local Authorities do?

Of course, local authorities are also uniquely placed to facilitate decarbonisation beyond that of their own buildings and assets. Of those authorities that have declared climate emergencies, the majority are setting net-zero carbon targets of 2030, well ahead of the UK government’s legally binding 2050 commitment.

This is a huge challenge and therefore every policy and development decision must contribute to these goals. (Climate emergency: time for planning to get on the case, 2022). There are perceived inadequacies in the Government’s National Planning Policy Framework (NPPF) and the recent changes to the Building Regulations, including the Future Homes Standard for 2025. National policy lags behind changes in climate legislation, hampering the ability of local authorities to enforce climate targets and there are calls to ensure that new developments demonstrate reductions in wholelife carbon emissions.

A recent House of Commons Environmental Audit Committee (EAC) Report acknowledged the need to set policy and standards relating to the assessment of wholelife carbon in buildings. The result is ‘Part Z,’ a proposed Building Regulations amendment which will require the assessment of wholelife carbon emissions, and limiting of embodied carbon emissions, for all major building projects. (House of Commons Environmental Audit Committee, 2022)

The impact of local government and authorities is therefore twofold:

- Mandating standards for net zero carbon development and wholelife assessment in adopted Local Plans, beyond national policy. There are few local authorities that have already taken such measures and there are advocates for rolling out the Greater London Authority’s recently adopted approach as national policy.

- Making wholelife carbon a fundamental consideration in the briefing and procurement of public sector construction projects, design teams, contractors, and supply chains.

Short-, medium- and long-term actions should be defined showing the direct impact local authorities can have, be that:

- Policy on wholelife, net-zero carbon buildings

- Identifying where they can work with their residents, businesses, and institutions on the improved thermal efficiency of buildings.

- Where they need national support by lobbying and communicating on the need to increase direct funding for net-zero carbon initiatives.

The UK government has allocated £6,6bn of funding to decarbonise buildings, of which over £2bn is aimed at low-income households. Phase 3 of the Public Sector Decarbonisation Scheme is providing £1.425 billion of grant funding over the financial years 2022/2023 to 2024/2025. It supports the aim of reducing emissions from public sector buildings by 75% by 2037, compared to a 2017 baseline. The guidance for the next application window, Phase 3b, will be published in July, with the application window planned to open in September 2022.

With climate deadlines looming and the effects of climate change already being felt, urgent action is needed.

Are you up for the challenge?