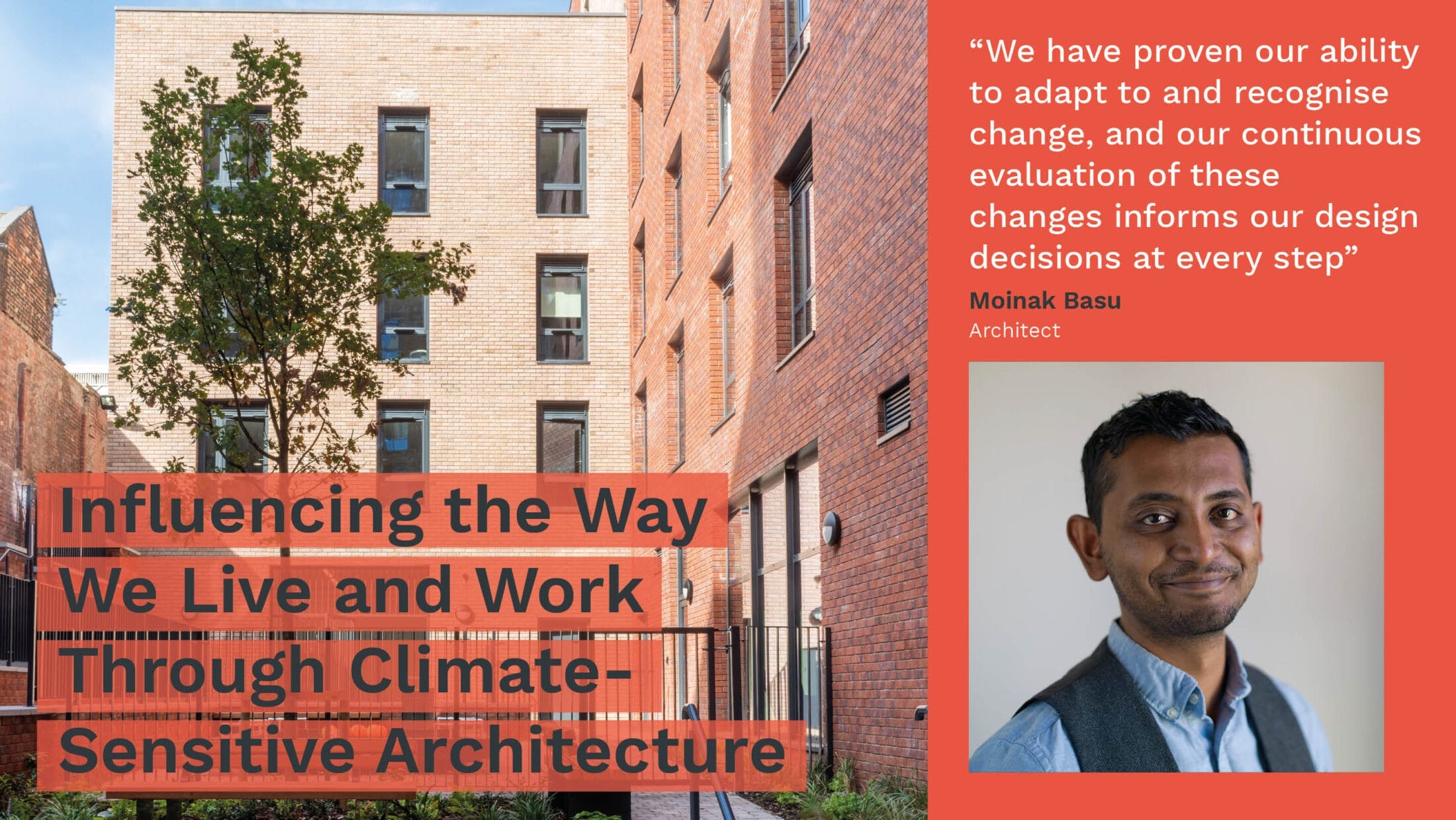

Our sustainability series continues this week with Architect, Moinak Basu, sharing his thoughts on how the pandemic has affected workplaces, and how we need to adapt our lives in order to create more balanced environments for the future.

“In the knowledge that businesses can be successful with colleagues working from home, a café, or even a park bench, the future of the workplace is largely unknown. This creates a need to reassess the nature of the workplace and its future.”

Due to the pandemic, we can now celebrate our ability at being ‘fully connected’ working from home. Innovation drives change – so does desperation, as evidenced by the pandemic. In the future, it may be both. Being digitally connected could mean we risk losing the connection that physically shared environments offer. Whilst we all wondered how beneficial working from home pre-covid would be, over the duration it has become clearer than ever that as social animals we need to be able to come into work, socialise and interact away from digital space for our health and wellbeing from time to time.

In the knowledge that businesses can be successful with colleagues working from home, a café, or even a park bench, the future of the workplace is largely unknown. This creates a need to reassess the nature of the workplace and its future.

Workplaces can – and should – adapt, possibly allowing for multiple businesses to share space, creating vibrant work environments. Business owners should influence and promote change by delivering spaces that are flexible, with good levels of ventilation, heating, and lighting; introducing biophilia; investigating the scope of incorporating green roofs (partially if possible), to help improve the centres’ Urban Greening Factor; and promoting cycle-to-work schemes and the use of public transport.

Coming out of the pandemic, as places of work reassess their rental agreements and start looking at smaller floor spaces to run their businesses, promoting a balanced approach to ‘working from home’, we need to keep an eye on what consequential impact this may have on urban centres. Will we be left with unoccupied spaces in buildings? Will this affect economic investment in the centre? If centres lose investment, would they then be attractive enough for the populace to be drawn to it? Shared workspaces could be the solution to many of these potential challenges. I feel the pandemic has illustrated our need to be social, and I am optimistic that even with homeworking and a strong work-life balance, the city centres as a hive of work and social activity will thrive.

To uplift ecological balance through the way we live, as individuals we require a greater understanding of our consumption and waste patterns, their consequential environmental impact, and what changes can be made to truly maintain and uplift natural and urban environments. Our homes should also afford us the ability to adapt them to the future changes in climate, allowing an adequate amount of outdoor space to promote the ‘biophilia effect’, and provide good access to daylight, ventilation, and heating to help promote health and wellbeing.

Growing up in the east, as a student of architecture I was fascinated by vernacular architecture which used local materials to build houses that worked for specific regions, in harmony with the environment. This typology did not depend on mechanical solutions (other than lighting) for providing comfort. The works of British-born Indian Architect Laurie Baker stood out as a beacon in my eyes. We have in the recent past created a definition of ‘modern’, and this does not sit well with the vernacular or in some cases showcase ‘respect for the environment’. Often, it requires the import of materials to climates and regions that want to exude a certain message by having to support it with unsustainable methods. Fortunately, as an industry we are talking more and more about climate-sensitive architecture and the promotion of circular economies in construction. I am hopeful that with further research and development we will be able de-strain the stresses that have been created.

Whilst the climate crisis has set off alarm bells, we can be cautiously optimistic that there is a significant amount of ongoing research and development to better understand how we can improve our built environment. We have proven our ability to adapt to and recognise change, and our continuous evaluation of these changes informs our design decisions at every step. We are bringing our understanding and expertise of climate-sensitive environmental design every time we bring pen to paper, and this will only improve over time.

Related posts