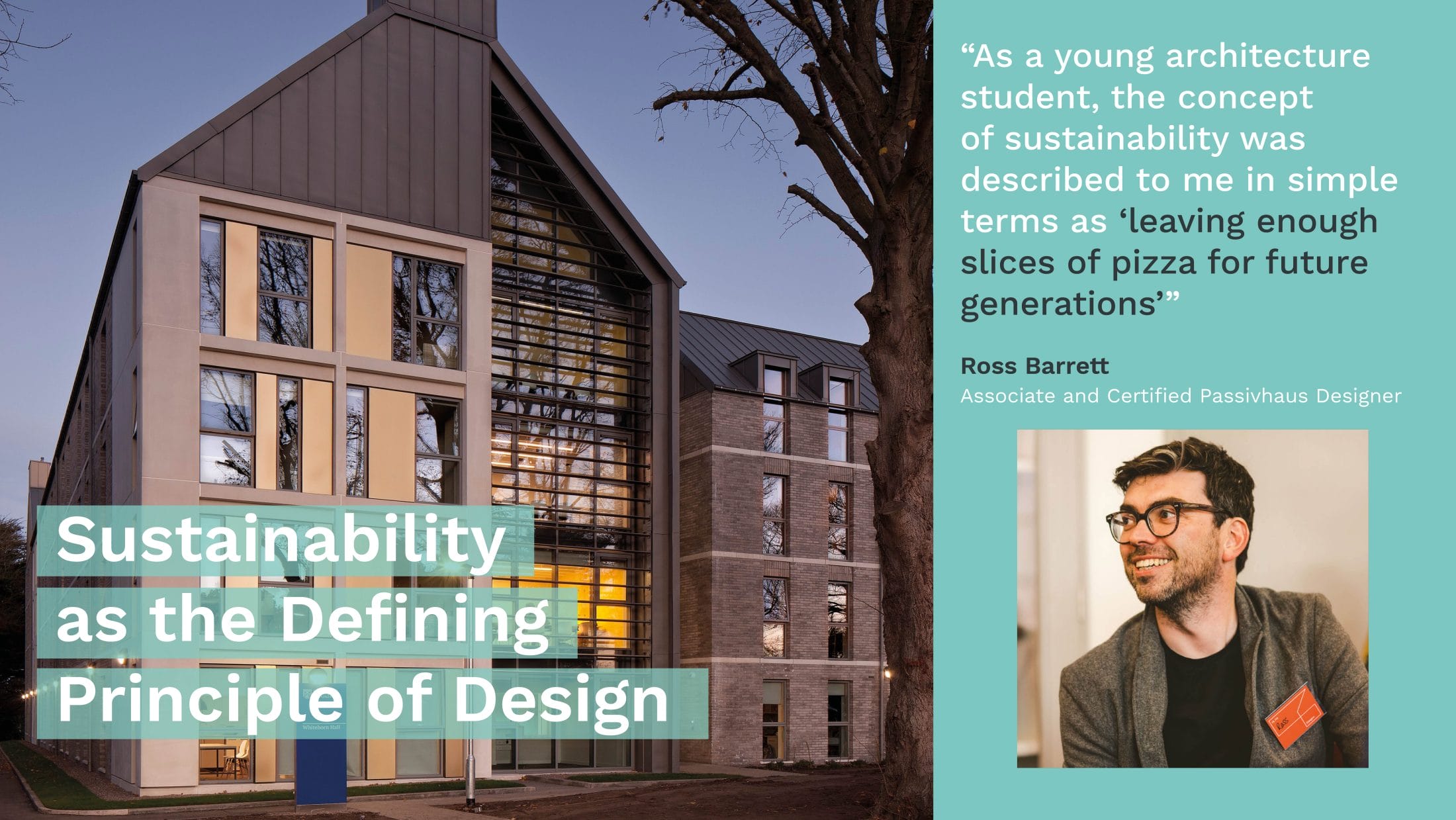

This week, Ross Barrett shares his experiences of how attitudes towards sustainability in construction have developed in the last 20 years, and how it needs to progress further in the present and future if we are to reach the sustainable outcomes.

As a young architecture student, the concept of sustainability was described to me in simple terms as “leaving enough slices of the pizza for future generations”!

Since I completed my degree nearly 20 years ago, our industry has developed a better understanding of what sustainability means. The declaration of a climate emergency, changing weather patterns, the rising cost of energy and the UN Climate Change Conference COP26 taking place in Glasgow in November 2021, have all helped to highlight the scale of the problem and focus minds.

I think it’s fair to say that in 2021, we now have much of the knowledge and tools at our disposal to design, build, and retrofit to reduce our carbon emissions, and create buildings and landscapes that are climate resilient and can adapt with our changing climate.

LETI, ACAN, Architects Declare, Passivhaus Trust, the RIBA with their updated Sustainable Outcomes Guide 2030, amongst many other organisations are doing a fantastic job of raising awareness around climate literacy. Their publishing of metrics, alongside sharing research and developing tools are helping to further equip the profession and put us on a more structured path towards net zero.

Despite all these advances, it would still appear that the industry is lagging. Perhaps it’s because sustainability is competing in the ever more complex world of construction where procurement, regulatory changes, navigating planning policy, recruitment pressures, low fees, material shortages, and dare I mention Brexit, can consume so much brain power. The process of architecture and building is complex; the more we try to make buildings sustainable and emit less carbon, the more challenges there are – and the more difficult it can become.

In this context, it is not surprising that sustainability is still fighting for prime position at the forefront of all architectural minds, yet we know that we all need to act collectively now, to limit increases in global warming. The 2020s is the most critical decade for the climate; we are on the verge of irreversible climate breakdown and biodiversity loss.

So, let’s use the skills we have and harness the knowledge that exists. As the foreword to LETI’s Climate Emergency Design Guide says, ‘it’s time to get sustainability done’. We all have a role to play, and we need to work together.

At HLM, we are upskilling our team in sustainability, Passivhaus, and Retrofit. We are also undertaking research, developing, and testing our own sustainability and post-occupancy evaluation tools, as well as sharing knowledge around metrics and outcomes. Our ambition is to ensure the whole HLM team can take the same creative, holistic, sustainable approach at every opportunity, creating a feedback loop to learn from our projects.

We need our teams to have the skills and knowledge base to ask the right questions, and perhaps have the difficult conversations with clients and design teams about doing more and going further. Questioning perhaps why we might not target bolder objectives at the outset of a project or to confidently (with the right data) for example put forward solutions that reduce carbon, increase biodiversity or tackle climate resilience over the whole life of a project.

As architects, we need to seize this opportunity to lead from the front, to influence, to help drive the sustainability agenda harder, and to develop creative solutions and practical outcomes that move to net-zero. We also need to help our clients better understand the value proposition of zero carbon buildings.

It is therefore imperative in my view that we change our priorities, starting with sustainability as the defining principle from the outset of every project. I believe that we need to make almost every decision on a building informed by, and focussed on, sustainability outcomes.

We must therefore start sustainability conversations early, appoint sustainability champions, prioritise passive design (including adopting the Passivhaus standard), we need to measure and benchmark embodied carbon to make informed decisions, retrofit existing buildings where we can, build in metrics to building contracts and adopt soft landings and the new RIBA plan for use.

We need to rethink how we operate and only by doing so meaningfully, can we really support our built environment’s transition to net zero.

To borrow a phrase, it’s no longer business as usual. We need to leave some pizza.