In the penultimate article in our sustainability series, Rebecca Ball explores sustainability in education, and why policy surrounding it needs to change if future generations are to minimise their footprint on the planet.

“Whilst we wait for the Bill to be consulted on and more papers to be written the real ‘leaders for sustainability’ will be parents at home who decide to take a lead on the conversations that we should all be having with our children.”

Last week, my nine-year-old daughter asked me, completely out of the blue, if we needed to change our cars to electric ones and if so, why hadn’t we done this. I was a little taken aback by the question. What had prompted this? Had she talked about it in school or seen an advert on TV? I explained what the government targets were, and how car manufacturers were working on making it easier for all families to have electric cars. Fortunately, she seemed satisfied with my answer, for now!

But it made me start to think how many other parts of our normal, everyday family lives do our children question and wonder why we do it the way we do? Will they hold us accountable further down the line for the things we’re doing and not doing now in relation to climate change? Probably!

As a parent of two young children, to me, sustainability now means taking personal responsibility for caring for our planet, bit by bit, habit reform by habit reform, to ensure that there still is a planet for future generations. We all know that simple adjustments to our everyday lives we make now can make big differences later and have positive, lasting effects on the environment we live in – it’s our social responsibility and we owe it to our children to do what we have to do.

From Phoebe’s question, I began to think much more about how we could work towards sustainability together as a family. As a Sustainability Champion at HLM Architects and Marketing and Communications Lead, I’ve witnessed first-hand the growing awareness of the impact of the built environment on climate change, and as a consequence, our health and wellbeing. Demand for more sustainable buildings with excellent health and wellbeing metrics adding real value to society is growing. The public are demanding better, businesses are demanding better, clients are demanding better, and we must be in a position as humans to live and behave appropriately in a more sustainable environment. It’s promising to see projects being commissioned to standards significantly higher than the current government regulations require. Local government is leading the way with some councils demanding the highest standards, for example Passivhaus, as they develop plans for their cities and boroughs to become carbon neutral.

Being thrown into home-schooling, although a logistical nightmare at times, gave me the opportunity to connect with my children in a different way, gaining a greater insight into their learning and their minds. It became clear how, not only do these younger minds see things in a different way they also see things that we, as adults who are influenced by our experiences, do not. It made me think about how adults could benefit from taking the children’s lead as to how they see the world and how we can improve it

But before I took the lead from them, I wanted to understand what they were learning about sustainability at school and what was included in the current curriculum. I was a little surprised with what I discovered.

Currently, children are taught about climate change and the environment in several different subjects, for example science and geography. However, there is only minimal guidance along the lines of emphasising that schools ‘have the freedom to pursue these areas if they wished’. The result is an inconsistent nationwide approach to teaching sustainability in schools, with many children leaving school not connecting their knowledge with the action they can take. This must change if schools are to reflect the future we all want.

At COP26, the Department for Education announced its draft Sustainability and Climate Change Strategy which outlined five ‘Action Areas’:

- Climate education

- Green skills and careers

- The education estate

- Operations and supply chains

- Data

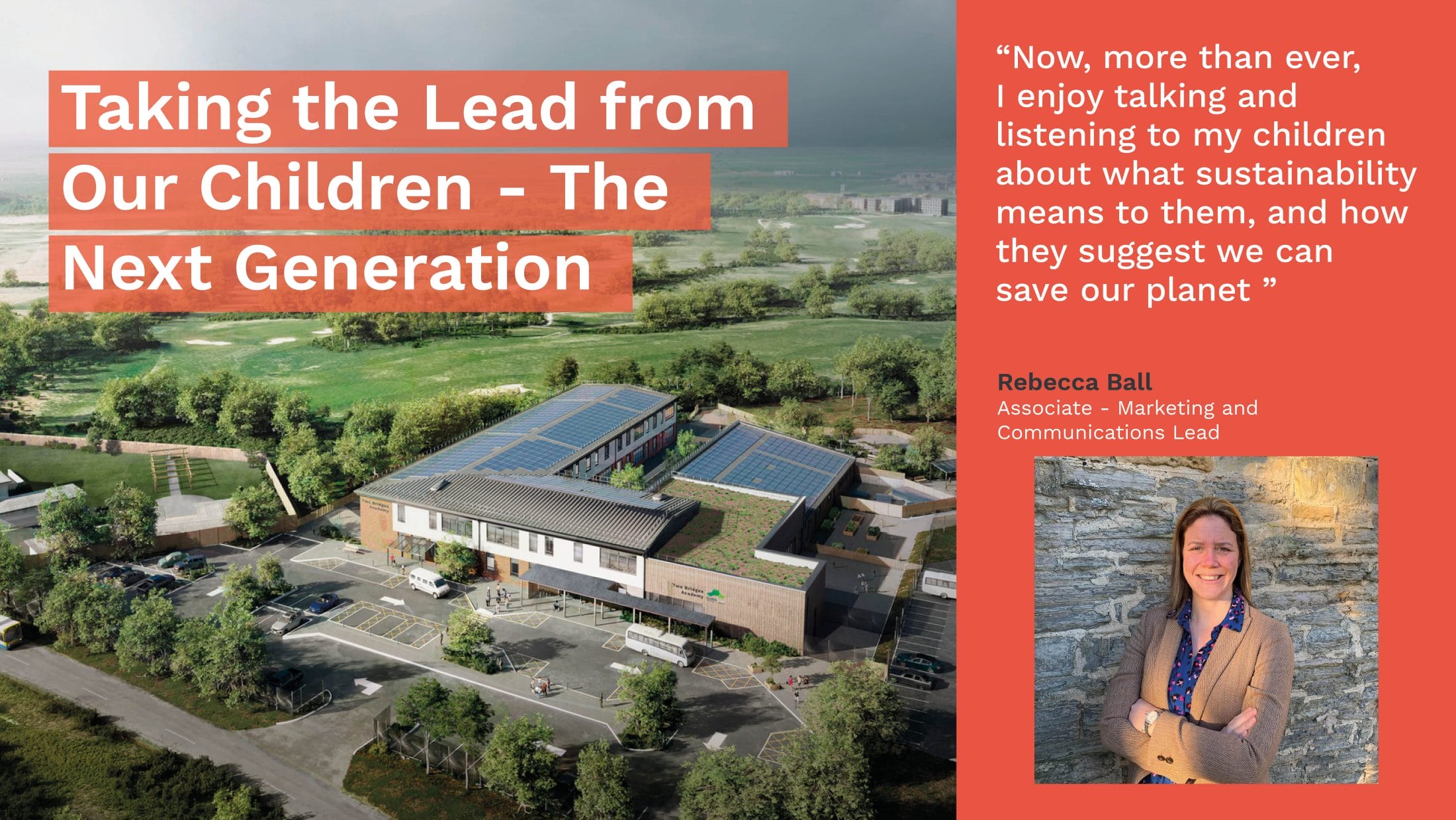

The third action, ‘The education estate’ aims to achieve a green, sustainable education estate that is resilient to the impacts of climate change and normalise and inspire young people to live sustainable lives, with impact felt widely in their families and communities. I see every day the great work that our education team are doing to create and deliver the government’s pledge for every new school delivered under the department’s school rebuilding programme to be cleaner, greener and net-zero in operation. Two Bridges Academy situated on South Gloucestershire is a great example of our most recent work on behalf of Department of Education through the Construction Framework. Whilst we can create these amazingly sustainable buildings for our children to learn in, it’s also essential that we teach them why we’ve done this, and more importantly, how to live and act in a more sustainable built environment.

In September 2020, a report by the Climate Assembly included the recommendation that climate change should be made a compulsory subject in all schools. The Education (Environment and Sustainable Citizenship) Bill aims to make climate change and sustainable citizenship part of the national curriculum taught in schools across England.

The bill would amend the Education Act 2002 so that the national curriculum includes education on the environment and sustainable citizenship. A general provision would apply throughout key stages 1–4 (ages 5–16). Lord Knight said:

“In order for Britain to meet its commitments to reduce our carbon consumption, we need significant behaviour change by the general public. Schools are the best place to start this work because young people and their teachers are especially motivated to want to take action to safeguard their futures. They are then significant influencers on their parents and grandparents.

In late 2018, a speech by Greta Thunberg, the environmental activist, to the United Nations Climate Change Conference (COP 24) went viral. Since then, the involvement of schoolchildren in climate change protests and climate action has prompted several commentators to emphasise the leading role that greater environmental awareness in education could have.

Whilst it’s encouraging to see the bill to amend the Education Act 2002, it is also frustrating to learn that since Greta took to the stage and so passionately spoke about her fears for the future, we still have not made any solid changes to our curriculum.

Whilst we wait for the Bill to be consulted on and more papers to be written the real ‘leaders for sustainability’ will be parents at home who decide to take a lead on the conversations that we should all be having with our children.

Like many people, COP26 drew me in not just because of the work that I do but because of my family and how the discussions and decisions there could impact us. Now, more than ever, I enjoy talking and listening to my children about what sustainability means to them and how they suggest we can save our planet, like Superman – not that they’re old enough to know who he is! We’ve now written our list of ‘sustainability’ goals that we want to achieve. These include growing more than just tomatoes, recycling plastic bottles and using the umpteen amount of reusable drinking bottles we have stored in the cupboard rather than buy a drink from the shop, turn off the lights so we don’t look like the landing strip at Heathrow airport anymore, accept that its ok to be a bit colder indoors and reach for a jumper not the thermostat. It’s a small step in the right direction, and who knows, if we manage to save money on our heating and electricity bills, then maybe we can save up enough for that new electric car.