How can we design hospitals for increased efficiency, while maintaining a level of personal space and privacy for patients? Kevin O’Neill talks about HLM’s pioneering design of the eight-bed cluster in the below article, published in the Health Estates Journal earlier this month.

When thinking of hospitals, many people might imagine an historic, clinical, or even anxiety-inducing environment. Designed with medical function in mind, a sense of welcome or attractiveness sometimes takes a back seat.

However, it is possible to help these spaces perform even better in the delivery of their intended function – the provision of high-quality care and treatment – while also making them inviting places that enhance the experience of patients, employees and visitors. This requires careful consideration when it comes to hospital design, and a vital part of that hinges on reimagining our approach to the traditional layout of wards and patient accommodation.

“The stand-out feature of the North Wing at Altnagelvin is the eight-bed cluster layout for the 144 single bedrooms, a unique concept within healthcare design leading to more efficient and carefully considered space planning that we don’t believe has been seen elsewhere”

Transforming the old view of hospitals

Hospitals have been planned in the same way for many decades. One notable change is the transition from the traditional Nightingale style, multi-bed ‘dormitory’ style wards, towards single room occupancy. Whilst there are many opinions within healthcare regarding the pros and cons of single room occupancy, there is no argument that a single bedroom not only affords more privacy but also helps reduce the risk of infection and is, at many times, necessary for those with more serious conditions who need closer monitoring in recovery. This need has never been more highlighted than following the recent Covid-19 pandemic.

Within the design of a single bedroom there are several room types that have been well developed through the HBN 04-01 and the NHS’s repeatable rooms programme, which tend to follow a typical design format. Some of the most common types of private room and ensuite arrangements for inpatient wards include the ‘inboard’ approach, which maximises opportunities for external windows and for natural light but has an obstructed view of bedheads for nursing staff; and ‘outboard’, which offers unobstructed views of bedheads but, on the flip side, reduces scope for external windows and opportunities for natural light.

North Wing at Altnagelvin

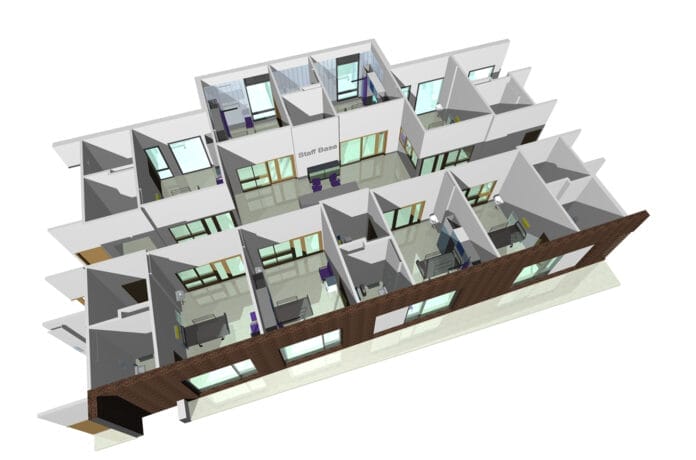

At HLM Architects, our team worked on the design and construction of the new North Wing development at Altnagelvin Hospital in Derry, Northern Ireland. The stand-out feature of this project is the eight-bed cluster layout for the 144 single bedrooms, a unique concept within healthcare design leading to more efficient and carefully considered space planning that we don’t believe has been seen elsewhere. This was achieved using a third room type to those mentioned above, the ‘interstitial’ layout. Within a repeatable layout, these rooms are often used within a typical format of two single bedrooms with two centrally interlocking ensuites.

With thoughtful planning and consideration of the placement of the bedheads and ensuites within each room, at HLM we have adapted the typical format for an ‘interstitial’ layout to form a cluster of eight bedrooms. By offsetting two of the bedrooms, we were able to create an area which provides the nursing staff with 100% unobstructed observation of all patients within the cluster from one central nursing station. The layout also allows us to maximise natural daylight and encourage patients’ connection to the outside landscape, as well as optimising secondary natural light within the corridors. Along with reducing travel times significantly for nursing staff, these were our key objectives.

An easy-to navigate space

A new main entrance further reinforces the vision of creating an easy-to-navigate, transparent and light-filled space, achieved through the design of a naturally lit atrium with a three-storey curtain wall. Another essential feature is the inclusion of internal courtyards, which form the basis around which wards are clustered.

The hugely positive impact of ample natural daylight and views of trees in healthcare design is well researched and is made possible by the reduced depth of the floor plan and single corridor layout in the Altnagelvin example. Biophilic design principles that enable greater access to views of greenery have also been widely shown to improve the wellbeing of patients and staff, accelerate healing and reduce stress. The fantastic NHS Forest initiative, for instance, which champions more tree planting in hospital settings, has found that being in close proximity to trees and plants really does result in faster recovery in patients, lowering the need for painkillers and leading to shorter post-operative stays in hospital [1]. Moreover, it creates a bright and airy feel, resulting in a less ‘sterile’ and more welcoming, reassuring environment. Not to mention the many knock-on sustainability benefits such as cleaner, better quality air.

[1] NHS Forest website – ‘Tree planting in hospitals’

“By maximising visibility of every bed from a single nursing hub, staff can save valuable and crucial time from making many rounds of the ward and can monitor multiple patients at once. It means they can direct their focus and efforts to where they are most needed. Additionally, patients gain the reassurance that they can be seen by a nurse at all times.”

Designing for optimal flexibility and efficiency

Adopting an ‘eight-bed cluster’ model can drive substantial efficiencies, and the overall flexibility afforded by this floor plan allows wards to cater to changing patient demographics and future shifts in demand and operational patient care needs. For instance, ward sizes can be adapted to 16, 24, 32 or 48 bedrooms in sets of eight, able to change over the years to accommodate extra beds or additional needs. This feeds into wider ambitions for healthcare provision across the country.

As architects, we have a tremendous opportunity to embrace fresh and creative new design principles to meet today’s challenges. It is well-documented that the NHS is under considerable strain, not least because of widespread staff shortages. According to the latest official figures from NHS Digital, the vacancy rate for nursing staff has grown to almost 12% across England, totalling nearly 47,500 vacancies (up from 10.5% last year)[2]. In Northern Ireland, meanwhile, plans have been announced by the Health Minister to map out the next phase of rebuilding and transforming hospital services[3] with the aim of enabling patients to be seen more quickly and providing better quality care overall. There is also a pressing need to cut down on long waiting times and a consistent shortage of hospital beds in the NHS.

Helping to offset the imbalance

Measures that support faster recovery and instil greater flexibility into hospital wards from the outset can go a long way to helping offset the imbalance. We can play a big part in effecting this much-needed transformation, and using innovative design solutions for maximised space utilisation can help assist in addressing some of the current issues as well as delivering more future-ready hospitals.

By maximising visibility of every bed from a single nursing hub, staff can save valuable and crucial time from making many rounds of the ward and can monitor multiple patients at once. It means they can direct their focus and efforts to where they are most needed. Additionally, patients gain the reassurance that they can be seen by a nurse at all times. Another important factor that should be considered is that, in an aging population, we must ensure that best practice and well-researched design techniques are integrated to better accommodate patients who may have secondary underlying conditions such as dementia.

At Altnagelvin, we researched the key characteristics of cognitive and perceptual issues and actively introduced solutions into the design. The new wing’s integrated wayfinding strategy relies on the use of colour to identify routes and enable a more intuitive and cohesive flow through various spaces, based on nuances of human psychology. For instance, strong contrasting borders on the floors work to subconsciously direct patients to enter certain rooms while demarcating boundaries for others (i.e., utility or specialist rooms intended for staff access only). This is complemented by the integration of art features throughout, as a way of creating an even more stimulating, inspiring and attractive space that is conducive to healing and positivity.

One thing that is becoming abundantly clear is that outdated planning and design principles can no longer cater to the ever-evolving and fast-changing needs of the country’s healthcare industry. We are learning more and more about how the design of healthcare facilities can create a calming and aesthetically pleasing environment, thereby strengthening the therapeutic effects of hospital settings. Incorporating greater efficiencies in space planning and rethinking our approach to the layout of wards can support the provision of high-quality healthcare while making more appealing spaces, with the potential to bring significant and diverse benefits to all building users. For this to happen, we must move past old views of how hospitals should look and open ourselves up to the possibilities and far-reaching advantages of embracing pioneering new design.

[2] NHS Digital – ‘NHS Vacancy Statistics England April 2015 – September 2022 Experimental Statistics’

[3] Department of Health – ‘Swann announces design plan initiative for reshaping hospital care’, 16 June 2022