In our latest article, Associate and Heritage Architect, Matthew Morrish shares his thoughts on the historical significance of prefabricated design.

During the late 20th Century some caravan manufacturers evolved into modular building contractors (i.e. Rollalong) and although prefabricated buildings and the first purpose-built leisure caravans emerged in the 19th century, both have become more widely available post-WWII, with the offsite assembly of whole rooms and building modules as permanent structures being even more recent.

After 1945 some aircraft fabricators transitioned into mass prefabricated housing production using aluminium and timber framing for homes that were meant to be in use for 10-15 years and many remain occupied. Some of the houses in Birmingham and London were listed by Historic England in 1998, their architectural, historical and social significance having been recognised. It’s thought that beyond the 1000-2000 prefab homes still being lived in many more have been refurbished and reclad by subsequent owners – becoming indistinguishable from other bungalows, their origins concealed from view.

Historic England’s A Brief History of Prefabs – The Historic England Blog describes how temporary housing dealt with the nation’s immediate needs but the emergence of permanent prefabs usually meant innovative lightweight panellised cladding upon a frame of steel, iron, timber or concrete, the elements brought to and assembled upon a prepared site. Industrialists, builders, engineers and architects collaborated to build nearly 500,000 permanent homes in the decade after WWII using various forms of prefabrication.

The first secondary modern secondary school by the Ministry of Education’s Development Group was St Crispin’s, built in 1952-3 and GII listed since 1993, it was the prototype for a multi-storey prefabricated school, becoming their most visited school due to it’s enlightened informal arrangement of education spaces and activities.

First Modern Prefabricated Secondary School

Hospitals and schools were needed to serve the new suburbs and new towns. The first secondary modern secondary school by the Ministry of Education’s Development Group was St Crispin’s Wokingham, Berkshire. Designed in 1949-50 by David and Mary Medd and the polymath Michael Ventris, overseen by chief architect Stirrat Johnson-Marshall (later to found RMJM), built in 1952-3 and GII listed since 1993, it was the prototype for a multi-storey prefabricated school, becoming their most visited school due to it’s enlightened informal arrangement of education spaces and activities.

Scarcity of resources and labour as well as the pressures of time and money have led to pre-fabrication becoming popular at particular moments in history and the external envelope of St. Crispin’s is no exception – external panels of 1in thick pre-cast concrete sandwiching a 1in thick board of wood wool mounted on a 1 and half inch thick panel of cement and sawdust particle board, finished with 3/8in of plasterboard internally, all supported upon the 3ft 4in grid primary steel frame, providing an efficient material and spatial organisation for education.

Despite having been extended and altered in the 1960s, 1970s and 2010s, the significance of the panellised buildings and especially the four storey tower of offices at the core of St. Crispin’s school remain intact and the need for the school to accommodate many more pupils in the late 2020s ensured these buildings would have ongoing and meaningful use – something the Ministry of Education and conservationists would surely approve of – even if further changes were afoot.

Celebrating the heritage through new design

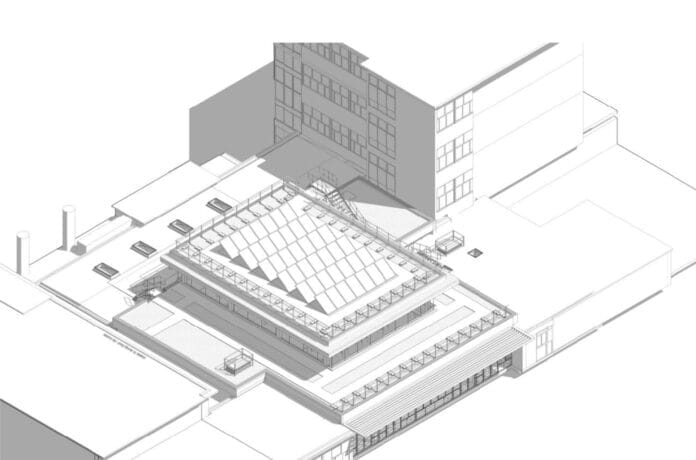

HLM have designed a much-needed dining hall expansion into a former courtyard at St. Crispin’s, incorporating a lantern roof with glazed clerestory, providing natural light and ventilation below a cross-laminated timber deck with a rainwater reservoir above, all sat upon exposed steel lattice trusses similar to those of the 1950 parts of the building. The courtyard addition stands back from the original four storey tower structure and emulates the lantern roofs to the original kitchen and changing rooms blocks which remain in use.

So as we take care of architecturally significant prefabricated buildings of the past, the prospect of an entirely modular modern (MMC) building eventually becoming a heritage asset is likely if it’s thought to have sufficient significance, even if the modules remain hidden behind a conventional façade and if evidence of prefabrication is subtle, significance value may well be found in future.

What is certain, is that alongside the re-use of existing buildings we will see well insulated, low-energy modular buildings also offering a solution to hitting tight carbon and cost budgets for a variety of activities and occupancies, and just as existing prefabricated structures have embodied carbon and social value for decades, modern methods of construction are likely to also deserve the unintended and unexpected benefit and protection of statutory listing in time.